This article examines the decisions of Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited and Minister for Education and Training [2016] AATA 1087 (23 December 2016); Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited v Minister for Education and Early Childhood Learning [2022] NSWSC 1176 (1 September 2022); and the appeal from the 2022 outing in Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited v Minister for Education and Early Learning [2023] NSWCA 143 (29 June 2023).

These decisions arise out of a common factual matrix but deal with distinct issues.

PART 1: Funding Compliance and lessons for Schools in dealing with related parties

In 2016, the Deputy President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (“AAT”) handed down his decision in Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited and Minister for Education and Training [2016] AATA 1087 (23 December 2016) – determining that Malek Fahd Islamic School (“the School”) had failed their funding compliance obligations by previously operating in a way that was inconsistent with the conditions of the government funding the School was receiving.

The School was receiving government grants in the form of “financial assistance” under the Australian Education Act 2013 (Cth) (“the Act”) on the basis that the School was operating in a not-for-profit manner and was a “fit and proper” entity.

During a portion of the time it was receiving the grants, the School was found to be: [i]

- making indirect distributions to the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils Inc. (its parent religious body) (“AFIC”) in the form of inflated rents paid in advance and in respect of services allegedly provided by AFIC;

- expending monies that improved the value of AFIC properties;

- applying its funds otherwise than for the purposes of the School; and

- providing loans to AFIC on “uncommercial” terms.

Takeaways

This case reinforced the need for Schools and Colleges to appropriately consider various factors when seeking to deal with its parental bodies and/or related charitable entities to ensure funding compliance – for example:

- All School expenditure must be solely for the advancement of the purposes of the School (proper purpose) which includes:

a. being necessary for that advancement; and

b. at not more than commercial rate cost (from the perspective of the School).

- Lease / Licence rentand charges by related entities must be necessary and be reasonable and commercial (supported by objective evidence). The length of tenure must also be reasonable and commercial (at least the useful life of buildings so not capital improving land belonging to someone else without reasonable rights of use);

- Loan Agreements, especially to related entities, should be approached with great caution. Commercial terms alone may not be enough (even if such terms include securities);

- Management / Services and charges by related entities must be necessary and on reasonable commercial terms;

- There should be written Board policies & practices about the above matters, consistently applied in accordance with their terms;

- Gifts to related entities should be minor and incidental (ideally from trading activities), including gifts to start a new school that is not a campus of an existing school – and then those gifts should only be for the purpose of advancing the school’s philosophy and aims;

- Conservatively, trading activities whose risks expose the assets of the School to liability should have some intrinsic connection with (in aid of / part of) operating a school.

- Governors of the College, who make decisions in the best interests of the College, should not be subject to direction from another entity.

PART 2: Failing to strictly comply with funding conditions, even after most non-compliance has been dealt with, may trigger FULL funding recovery rights

This part examines the decisions of Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited v Minister for Education and Early Childhood Learning [2022] NSWSC 1176 (1 September 2022).

The School again found itself in dispute with the New South Wales Minister for Education and Early Childhood Learning despite having made significant changes to its structure and governance. This dispute was over whether approximately $50,000 paid out in offence of the not-for-profit requirement in two years could result in the ability of the government to require the return of $11 million in funding for those two years (2014 and 2015) by reducing recurrent funding over the next five years. The Court at first instance and on appeal did not disturb the decision of the Minister.

This case was effectively about the meaning of the following provision in the Education Act 1990 (NSW) (the “Act”):

“83C Financial assistance not to be provided to schools that operate for profit

(1) The Minister must not provide financial assistance (whether under this Division or otherwise) to or for the benefit of a school that operates for profit. ….”

The “Act”, particularly under section 83J, enabled the Minister to take steps to recover “the amount of any financial assistance provided” to the School if the School was acting in a way that was not compliant with the Act’s financial assistance conditions.

The Court found that the words ’the amount of any financial assistance provided‘, “[are] intended to allow the Minister to recover “each amount of financial assistance”, or all of the different amounts provided.” (Paras 201 and 228).

The Court also found:

- Whilst the Minister had a discretion as to whether to recover a round of funding (for example recurrent funding in 2014), it was not a discretion as to partial recovery of a particular round of financial assistance provided, but that it was all or nothing of a particular round (Paras 229 -232);

- “If all that is to be recovered is the amount of “profit”, then schools utilising income for purposes other than the operation of the School would know that their only potential loss is the monies so used” (Para 247); and

- “The prohibition on the provision of financial assistance to schools that run for-profit or are non-compliant is absolute. While the Minister has a discretion not to recover monies paid to such schools, that is a discretion to ameliorate the effects of the absolute prohibition in appropriate circumstances” (Para 248).

The Court:

- dismissed each of the grounds of appeal put forward by the School;

- found in favour of the Minister; and

- ordered that the School pay the Minister’s costs.

PART 3: Appeal to the New South Wales Court of Appeal in relation to Limitation Act considerations

Malek Fahd appealed the findings of the Court in relation to the operation of the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW) (“Limitation Act”) in this matter. The appeal judgement is found at Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited v Minister for Education and Early Learning [2023] NSWCA 143 (29 June 2023)

Malek Fahd argued that because the School was operating for-profit in 2014-2015, and because the Minister did not decide to commence recovery of financial assistance from the School until March of 2021, the Limitation Act would prevent the Minister from pursuing such recovery. This was because the Limitation Act had a 6-year limitation window on taking action on a cause of action (see in particular sections 14(1) and 63).

Section 83J allowed the Minister to recover from non-compliant schools “an amount [of financial assistance]…:

a. as a debt in a court of competent jurisdiction, or

b. by reducing future amounts of financial assistance payable by the Minister to or for the benefit of the school concerned,

or both.”

The Minister took steps to the recover financial assistance pursuant to subclause (b).

The Court of Appeal found that Pt 3 Div 7 of the Education Act contained its own “self-contained provisions” relating to recovery of payments of financial assistance to non-compliant schools (para 8), and that the Minister making recoveries through subclause (b) did not engage the Limitation Act’s debt recovery limitation periods (paras 56-58).

Therefore, the Limitation Act did not apply to prevent the Minister from recovering, via reduction in future payments, the financial assistance provided to the School.

In obiter, the Court of Appeal also considered the case where the financial assistance was to be recovered as a debt through a Court. Contrary to the primary judge’s opinions (that the cause of action arose on a recommendation from the Advisory Council to make a non-compliance declaration against a school), the Court of Appeal found that the cause of action actually commenced when the Minister was satisfied “that a school had been the recipient of an unlawful payment, or that the school is otherwise a non-compliant school.” (Para 64).

As a result:

- the appeal was dismissed; and

- Malek Fahd was required to pay the Minister’s costs.

Takeaways

Strict compliance with the not-profit requirement is crucial. The payments in question were all related party payments. Therefore, well-maintained Related Party and Conflict of Interests policies and registers are essential to assisting schools in upholding their compliance obligations.

Relevance in other jurisdictions

This series of cases has relevance in states other than New South Wales.

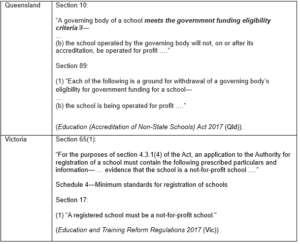

In Queensland and Victoria, for example, the relevant legislation in part provides:

This article was written by Andrew Lind and Jackson Litzow

DISCLAIMER: Corney & Lind Lawyers provides articles on its website for general and informative purposes only. Any articles on our website are not intended as, nor should they be taken as, constituting professional legal advice. If you have an issue that requires legal opinion, Corney & Lind Lawyers recommends you seek independent legal advice that is appropriately tailored to your circumstances from an appropriately qualified legal representative.

ENDNOTES

- [i] Malek Fahd Islamic School Limited and Minister for Education and Training [2016] AATA 1087 (23 December 2016), [29],[42]-[44].